Mount Wellington

Wellington Park, Hobart

Mount Wellington looms 1,271 metres (4169 feet) above Hobart. The mountain provides a jaw-dropping lookout accessible by car and several bushwalks, including The Organ Pipes.

These column-shaped cliffs were formed in the Jurassic period when Tasmania was separating from Antarctica. Mount Wellington is also one of the best (and easiest) places to enjoy the snow.

Mount Wellington is only a half-hour drive from Hobart, and you can often see the snow-capped peaks from within the city. You can also check the snow-cam for a better idea of the conditions. Or take the dedicated bus that takes you straight there.

Pinnacle Road will take you to the peak; it is a windy but safe overall, and it’s accessible by caravans and motorhomes.

There is no need for a Parks Pass, and entry is always free.

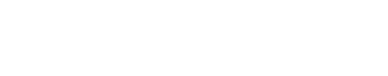

Where to stay in Hobart

Pulpit Lookout

Pulpit Rock Road, New Norfolk

Pulpit Rock Lookout gives you views of New Norfolk, framed by the Derwent River. You’ll see straight up the river, and to the surrounding rolling hills.

It’s a gravel road to the top, and it’s thin at times, so you must negotiate with other passing cars.

I *stupidly* got stuck driving to the top: I reversed into a gravel section on the hill to let another car pass; I had to be towed out. Just play it safe and you’ll be fine; my van isn’t well suited for off-road adventures.

Pulpit Lookout is a great location to watch the sunset.

Advertisement

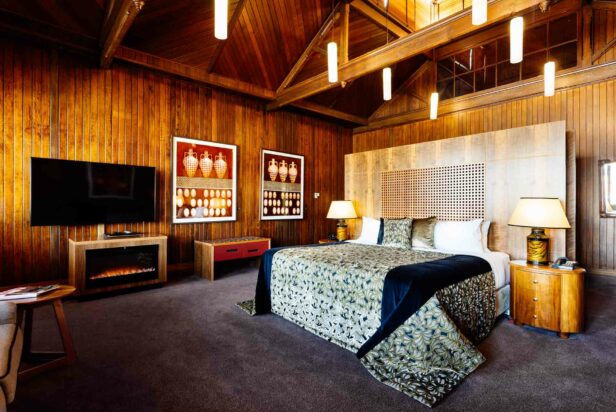

New Norfolk

Tasmania

New Norfolk was settled in 1807 when the first Norfolk Island settlement was closed. Mostly farming families migrated to Tasmania, with the promise of land grants in compensation. It’s the second largest town you’ll visit on your journey to Strahan; consider stocking up on goods while you are here.

New Norfolk has a collection of large antique stores; Willow Court Antique Store, Drill Hall Emporium and Ring Road Antique Centre. It is also home to the Agrarian Kitchen, a cooking school and restaurant with a strong reputation (and a pricey menu.) You’ll also find St Matthews, Tasmania’s oldest Anglican Church, and the Bush-Inn, one of Australia’s oldest pubs.

What you need to visit in New Norfolk is the Derwent River bank. I visited on a warm day, so I took a swim off the jetty. Ducks bobbed past, and the river reflected the blue sky; it was magical.

Take the Derwent River Cliff Walk from the caravan park. This will take you up some stairs and to an impressive lookout. You can continue on the walk, but honestly, just double back to the caravan park; it doesn’t get any more impressive.

The Welcome Swallow Brewery

Ring Road, New Norfolk

The Welcome Swallow Brewery feels a lot like the indie breweries of Melbourne; it’s inside an old warehouse, there are plants galore and the seats are an eclectic mix. Instead, this microbrewery is in the small town of New Norfolk.

The Welcome Swallow brews in limited 800-litre batches, with hops that they have lovingly grown themselves.

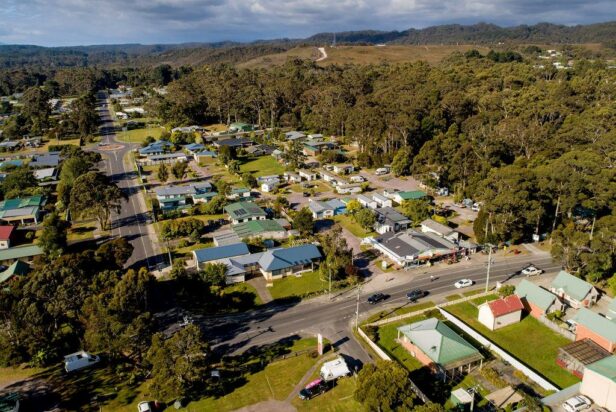

Salmon Ponds

Salmond Ponds Road, Plenty

To the European settlers, Tasmania was a very different region to the motherland they left behind. So they began introducing wildlife and fauna to make it seem like ‘home.’

The salmon ponds were an attempt to farm salmon, but they failed. Salmon are migratory fish, and after they hatched, they never returned to the Derwent. Instead, these ponds were used to breed trout.

Visit the Salmon Ponds and wander around the 19th-century English gardens, feed the trout and dine at the cafe.

Advertisement

Russell Falls

Mt Field

Russell Falls is the most impressive waterfall I have seen in Tasmania, and perhaps the most photographed in Tasmania.

Russell Falls was first discovered in 1856 and initially called Brownings Falls. Mount Fields soon became a popular destination and in 1885 it was protected as Tasmania’s first nature reserve.

Russell Falls is a short ten-minute walk from the carpark. I would recommend continuing on and climbing up to Horseshoe falls; a less impressive waterfall, but the climb gives you a great view of the park. From here you have the option of continuing to Lady Baron Falls and completing the Three Falls Circuit.

Personally I would recommend turning back to the carpark, Lady Baron Falls is average, and the full circuit will add at least an extra hour to your visit. If you love a bushwalk, do it; if you are pressed for time then skip it.

Important: You will need a Parks Pass to enter Russell Falls. You don’t need to show it to anyone upon entry, however it must be visible on your car.

Wall in the Wilderness

15352 Lyell Hwy, Derwent Bridge

The Wall in the Wilderness is an art project to commemorate those who shaped Tasmania’s central highlands. The huon pine slab stands three metres high and one hundred metres long, carved by sculptor Greg Duncan.

Engraved into the wood are timber harvesters, miners and hydro workers. The wall is open to tourists but take note! Photos are not allowed.

Donaghys Lookout

Southwest Tasmania

This forty-minute return walk will take you through forest and up to Donaghys Hill. From there, you look down on the Franklin River valley and out to the Frenchmans Cap. It’s a fantastic view and pretty much gives you 360 degree coverage.

It’s located midway between the Derwent Bridge and Queenstown, making it an excellent moment to stretch the legs.

When I climbed to the top it began to rain; there is no cover at the top so bring a raincoat/umbrella if you can.

Advertisement

Nelson Falls

Lyell Hwy, Queenstown

This short walk – off the Lyell Highway and thirty minutes from Queenstown – will take you to a gorgeous waterfall. It’s an easy walk and features a boardwalk accompanied by interpretation panels highlighting the unique plants in the area.

Be careful to walk on the middle of the boardwalk, the edges are slippery. There’s also a toilet next to the carpark if you need a dunny stop.

Iron Blow Lookout

Gormanston

The Iron Blow was established in 1883 on Mount Lynell. Prospectors had hoped to find gold, instead, they found a large amount of copper.

The area is now desolate, and while void of life, has its own unique beauty. The lookout will give you a view of the Iron Blow. There is plenty of parking and the lookout is easily accessed by foot.

Horsetail Falls

Queenstown

This thirty-minute walk will lead you to fantastic mountain views. Witnessing the falls is dependent on recent rainfall. Horsetail Falls is fed by small streams flowing from Mt Owens. it slows to a trickle during Summer, and during Winter can becomes a misty cascasde.

While pretty, Horsetail Falls aren’t as grandiose as Russell Falls or Nelson Falls. The main reason to tackle Horsetail Falls is for the view of the landscape.

Advertisement

99 Bends

Lyell Highway, Queenstown

This windy road will lead you to Queenstown. Despite its name, it doesn’t feature 99 bends, but there sure are a lot. The 99 Bends might sound intimidating, but it is a relatively easy drive; both cars and motorhomes will manage fine. I took my old van up and down several times, probably to the dismay of locals keen to overtake me.

While the speed limit is technically 100km/h, there is no way I would suggest reaching anywhere close to that; the drop off the side is steep. The 99 Bends features in TARGA Tasmania, an annual tarmac-based car race that takes competitors across the state.

Watch: Cruising down the 99 Bends

Queenstown

Queenstown

Like all towns on the West Coast, Queenstown has a long mining history. Visit the Galley Museum to get a better understanding of the trials of the Queenstown prospectors. Housed in an old pub, several rooms are filled with photographs and relics, all documenting the West Coast.

Queenstown also has a notable football field. Unlike traditional footy fields, this one isn’t covered in grass; it’s gravel.

It’s not easy to grow grass due to the contaminates left over from the mine and the West Coast’s large rainfalls – the town gets 2,408 mm of rain a year. Every year the council tips ten truckloads of gravel and compresses it with rolling machines.

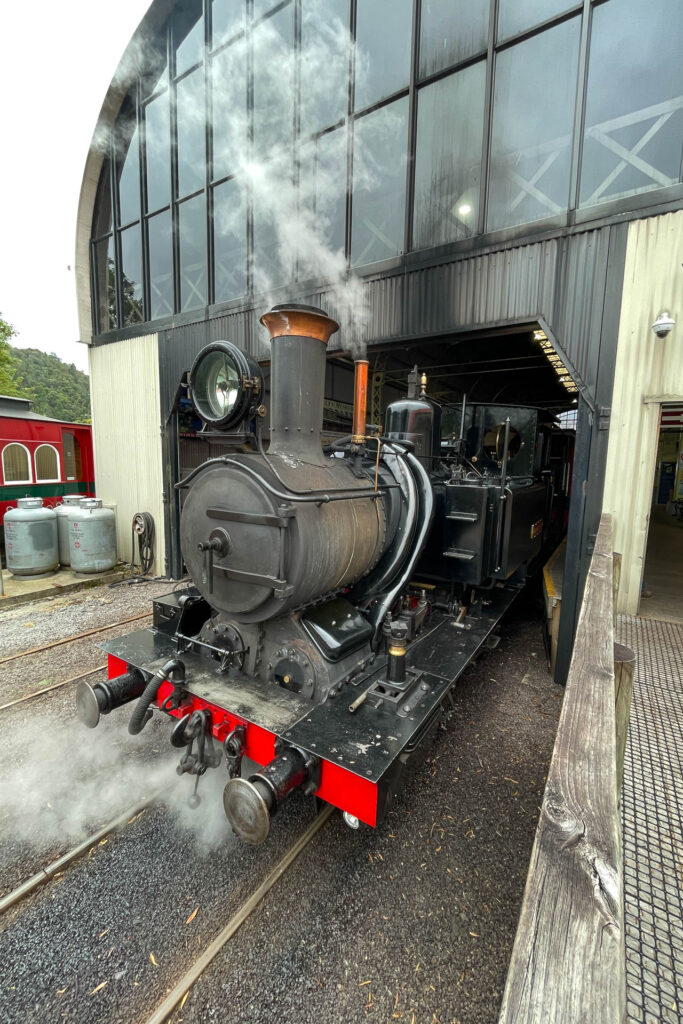

If you choose to pass through Queenstown and not stay the night, there are a couple of quick activities I’d recommend. Drop in for coffee (or lunch) at the Tracks Cafe, which is part of the Wilderness Railway. You can also explore the small museum and maybe catch the steam train leaving.

Then take a short drive up to Spion Kopf Lookout (Dutch for Spy Hill.) This lookout has ties to the Second Boer War back in 1899 and provides a nice lookout over the town towards the 99 Bends. There’s a couple of parking spots at the base, and it’s only a quick walk up.

Advertisement

Strahan

West Coast

Some say visiting Strahan is like visiting the edge of the world; this isolated harbour town sits on the edge of McQuarie Harbour and is surrounded by world heritage-listed wilderness. Although isolated, it is a gateway to several incredible experiences on Tasmania’s West Coast. The best coffee in town is from The Coffee Shack, just opposite the wharves.

Where to stay in Strahan

See more dealsTaylor was born and raised in Tasmania. He moved to Melbourne to study Film & television, and went on to start a marketing agency for hospitality.

He has a love for rock ‘n’ roll bars & New York-style pizza. In 2020 he was amongst the top 1% of Frank Sinatra listeners on Spotify.